This post was originally featured in the Heritage Institute’s 2016 Index of Culture and Opportunity.

I find myself asking people that I meet in the education reform field whether they can remember a time when they could not read.

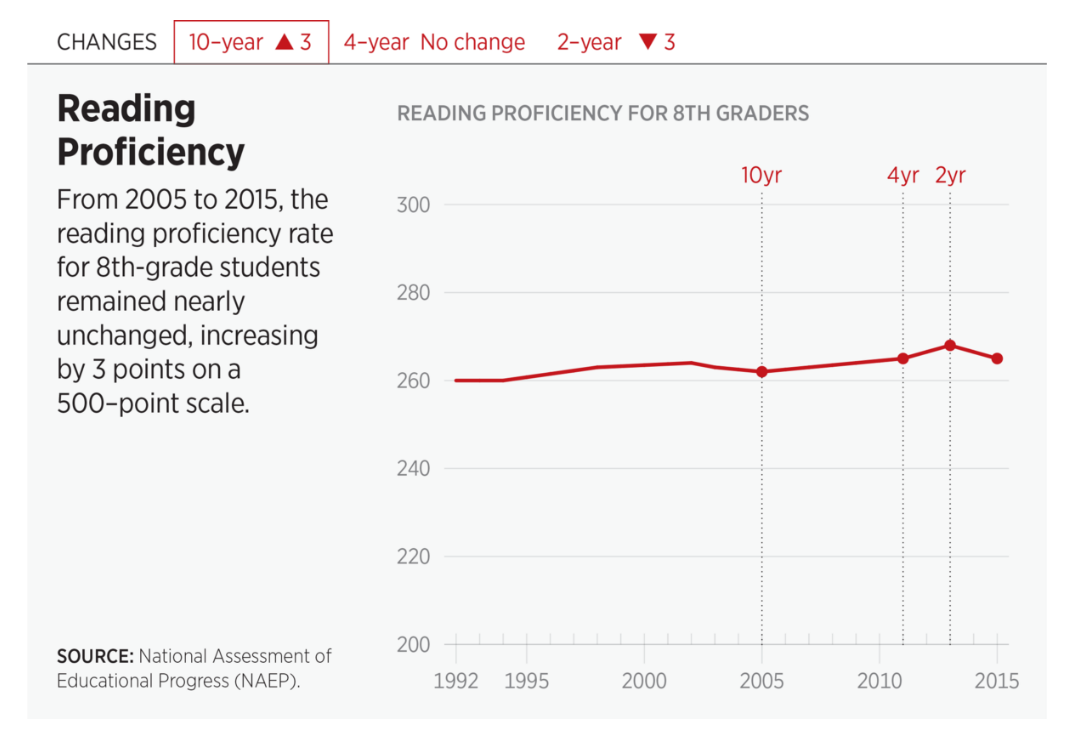

Acquiring the power to read is so monumental that it rewires the brain in a way that cannot be undone and leaves a person forever changed. It is the sort of synaptic magic that both improves the human condition and creates greater opportunity for those who can do it well — which is why the stagnation of the nation’s reading scores is troubling, even though they trend favorably on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP).

The story of a nation is a novel being written at all times and at all places. Its themes are powerful, and being able to access them — to read them — is crucial to our social identity. Our shared stories allow us to cooperate in groups larger than the tribal bands from which we descend.

These realities — these stories — make nations possible as they have made America possible. That more children are not being equipped to understand them at deeper levels is troubling. That we would overlook this stagnation is even more alarming. Finishing a book requires a continued turning of the pages. The story for us, it seems, is that reading achievement has been stuck on the same page for too many years.

Perhaps more important is how our children see themselves in the world and how reading shapes who they can and might be one day. Who were your literary heroes? What stories have stayed with you from childhood? How have those dreams set your life’s course?

My childhood was enchanted by the British and their myths, accessed through the fiction of long-dead authors whom I would never meet. The country’s origin story — a boy mentored by a wizard who pulls a sword from a stone — had the sort of electricity that inspires young people to read and dream. That I was inspired by Britain’s swords and dragons is not particularly unique. That it happened while I lived on a rugged corner of southwest Baltimore, however, is.

When children read, they open windows into futures that otherwise are closed. This is particularly important for low-income children — black, white, or other — as they struggle to imagine their own place in the world where what surrounds them seems deeply constricted. The kind of near-stasis we see in NAEP reading scores (a three-point gain over a decade) inspires little in the way of confidence if you care about these young people who have many obstacles to clear in the fight to become who they are meant to be.

On the other hand, there are schools that are obliterating this stagnation. In just a decade, for example, Success Academies in New York City have expanded from one school to 34, filled with 11,000 overwhelmingly black and Hispanic students whose test scores on reading (and mathematics) place them in the company of students in the most rarefied of America’s school districts. Choice unleashed “Success” — and similar examples of excellence across the country — in a way that traditional school bureaucracies either cannot or will not. That the force of choosing is powerful enough to bring this much excellence into the world this quickly is a lesson that everyone should take to heart.

If you believe we can and must do better for our children, NAEP reading scores are merely a glass that is half empty. That hope should drive all we do so that the next 10 years are not like those we have just finished.